“BYO laptops led to gaming, porn, gambling in class….” SMH April 2022.

You may have seen the article quoted. As a result of concerns about the misuse of digital technology, a well known Sydney school decided to abandon its BYOD policy because it was “sub-optimal to the learning of students”.

The “pile-on” in the comments section of the newspaper was predictable. (Note: I have corrected the spelling, punctuation, grammar etc of the comments used as examples)

- Time to admit what is overwhelmingly obvious to many people – internet availability in class, whether via phones or laptops, is a huge source of distraction and should be banned.

- BYOD has been a disaster for students’ education. It is a complete distraction and has also impacted learning with a “just Google” it and “do your own research “ online mentality in the classroom.

- This is happening at all schools – public and private. Distraction and lack of attention etc. Our kids’ brains are being ‘fried’ by online irrelevance. Nothing unexpected. I assume no one is surprised.

- Good move. Back to basics. Pen and paper. Learning is not by passive watching but actively writing things down.

Access to digital devices and the internet will always be an issue in school when teachers and parents are unwilling to monitor and regulate their use.

At the same time, banning or limiting their effective use will limit the capacity of these tools to be used to their greatest effect and is not a great way of preparing students for life after school.

All tools have the capacity to be misused and even dangerous in the hands of those not trained to use them appropriately, and digital tools are no exception.

When employer organisations complain, as they often do, that school graduates are not “work ready”, they are not just talking about a perceived literacy or numeracy deficit, they are talking about the capacity to exhibit responsibility, the capacity to access, analyse and use information and being able to be trusted.

Does banning BYOD increase work preparedness?

It seems that schools need to find a balance between using these tools effectively, and teaching students how to use them responsibly so that students are future ready both in terms of capacity to use digital tools and use them in an appropriate manner.

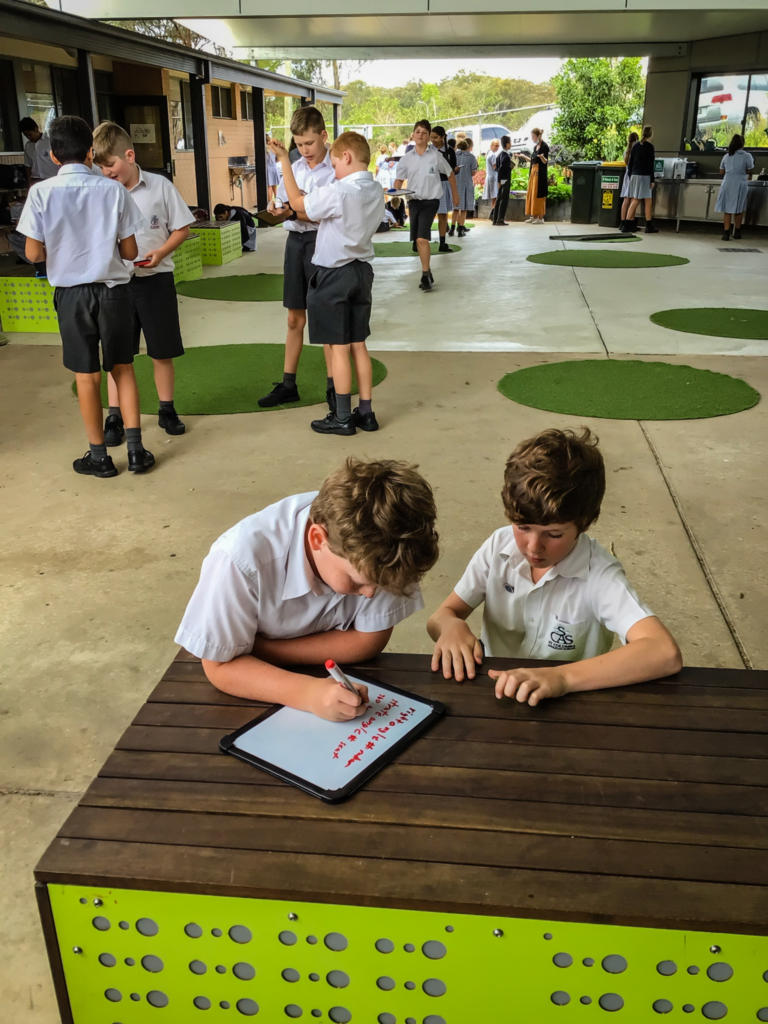

Why allow digital devices in schools? “The effective use of digital learning tools in classrooms can increase student engagement, help teachers improve their lesson plans, and facilitate personalised learning. It also helps students build essential 21st-century skills.”

A few questions I considered when thinking about this issue:

- Is this a real problem schools face? Yes, but one that can be addressed by effective classroom management, better teaching strategies and effective monitoring by the school and parents.

- How do we balance our response to the relatively few students who misuse digital technology at our school against the potential educational benefits of digital technology? We deal with those we find breaking our rules and support those who do the right thing.

- Will abandoning a BYOD policy and replacing it with a school-provided device end the problem of misuse of digital devices? Probably not, as students know how to use phones and other devices to get around school imposed limits.

Maybe we need to get the balance right, rather than apply knee-jerk reactions to changes in our world and our educational approach.

I will leave the last words on this matter to the NSW Government’s Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation, rather than armchair critics:

The issue of mobile digital devices in schools is one that continues to receive considerable attention in the media, in schools and among commentators. There is growing concern about the impact that non-educational use of mobile digital devices in schools can have on student wellbeing. The evidence behind the effect of mobile digital devices on student wellbeing in schools is both mixed and limited. There is some evidence that cyberbullying is increasing, but this link cannot be directly attributed to mobile digital device use in school. There is also evidence that phones do distract students from learning, although this evidence largely comes from studies undertaken at the tertiary level. The evidence in terms of sexting points to the fact that teenagers are not sexting as much as other young adults, and that when they do it is often in the context of perceived mutual trust. Some evidence shows that use of mobile digital devices may hinder social interaction which can lead to lower levels of psychological wellbeing, but other research shows that mobile digital device use may enhance important peer and family relationships. The same mix of evidence is found with regard to mental and physical health. In terms of the most effective response to mobile digital devices in schools, the evidence similarly varies. There is some evidence that banning mobile phones may improve academic outcomes for low-achieving students, but other evidence shows that students are adept at ‘getting around’ bans on mobile digital device use in schools. Other researchers state that a ban is not the answer, that students need to be taught ‘digital literacy’ instead, and that mobile digital devices will simply be subsumed within existing school regulations and controls.

Want to share your thoughts on this story, or do you have something you’d like to add? Email me at principal@scas.nsw.edu.au